There is a green Commonwealth War Graves Commission sign on the gate of the Oude Algemene Begraafplaats on the Keern. It indicates that four aviators from the United Kingdom are buried in this cemetery. They were killed in two separate air crashes above the IJsselmeer, one crash in the night of 15 and 16 February 1944 and the other in the night of 5 and 6 June 1944.

These are the names of the Englishmen who fought for our freedom, yet never to return home themselves:

Sergeant Jack Ratcliffe, 25 years-old

Sergeant David John Young, 21 years-old

Flight Lieutenant Victor George Brewis, 28 years-old

Flight Lieutenant Arthur Whitten Brown, 22 years-old

On Tuesday 15 February at 17:28 hrs, the Avro Lancaster LL689 takes off from Witchford Cambridgeshire, England. Its mission is to bombard Berlin. The heavy bomber, carrying seven crew members on board, arrives above the IJsselmeer at around 23:20, southeast to the village of Schellinkhout. There the bomber is intercepted by a German night-fighter aeroplane, the Messerschmitt BF 110 G-4, piloted by Heinz Wolfgang Schnauffer. However, this interception was no coincidence…

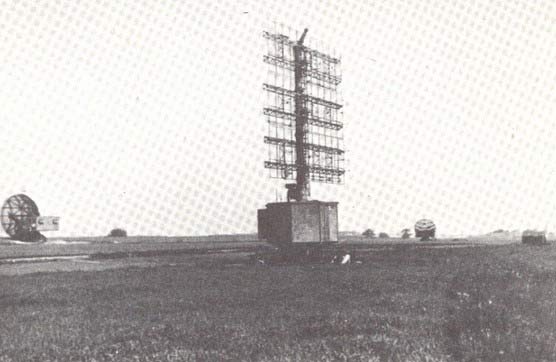

For the Germans are furnished with very good radar equipment and many listening posts – one of which is situated in Medemblik. This radar system functioned so well, that the occupying force picked up the signals of the English aircrafts fairly soon after they had taken off. In all probability, the Messerschmidt took off from its German base in Leeuwarden as soon as the Lancaster appeared on the radar. This radar was able to narrow down the exact location of the English aircraft, with a margin of just 100 metres. From this distance onwards, a German pilot would have been able to see the red-hot exhausts of the engine motors with his own eyes. The Germans named this very effective air-defence system the so-called ‘Himmelbett-Verfahren’ technique, because of the way in which the radar hung across various countries like the bed-curtain of a four-poster bed.

In the night of 15 and 16 February, the German air-defence system proved fateful for the Lancaster as well. The bomber is brought down by the Messerschmidt and the English plane crashes into the IJsselmeer as it burns. Acting mayor Mol of Schellinkhout records this fatal crash as follows (see also www.geschiedenisschellinkhout.nl):

“On February 15, 1944 at 23:30, an aeroplane was shot down above the municipality of Schellinkhout. The plane crashed into the IJsselmeer as it burned (some 1000 metres off the coast). Three parachutes have been sighted. There has been no damage to property. No aircraft parts have been found. The German Kriegsmarine have searched the IJsselmeer for drowned bodies and wreckage. It is likely to have been a four-motor English aeroplane. Two Canadian members of the crew have been saved. Messages were delivered via telephone to:

- De Rijksinspectie Luchtbescherming Den Haag;

- Den Beauftragte des Reichskommissars für die Provinz NordHolland (Polizei-offizier) in Amsterdam. The Ortskommandant in Hoorn could not be reached via telephone.”

This website also notes the following: “The time of the crash is stated as 23:19 hrs. The crashed aeroplane is a Lancaster II type, belonging to the 115th Squadron. The serialnumbers are LL689 / T 3416. First Captain is F/Sgt. J.W. Ralph. According to the announcement of Piet Baas jr. the wreck of this aeroplane has been salvaged by the authorities in 1947.

(Note: the report notes two Canadians to have been in the aircraft. This is not right, only Flt/Sgt Tomlin possessed the Canadian Nationality. The other crew members were British Nationals.)

Jack Ratcliffe’s tombstone and a portret of David John Young

Even though English fighter planes often carry a rubber boat on board (containing basic necessities) in case of a crash in water, this was no longer a viable means of rescue. Two crewmembers of the Lancaster – John Johnstone and J.D. Tomlin – hanging from their parachutes, end up approximately 100 metres off the coast of Schellinkhout in the IJsselmeer water which is very shallow there. There they stand submerged to their bellies in water, suffering from burns. Not knowing where to go in the dark, disorientated as they are, they call for help. The Germans, having arrived by then, pick them up from the water and take them as prisoners of war. Both end up in the POW camp Stalag Kopernicus 357, but they do survive the war.

This is not the case for the other crew members. The bodies of two of them – Jack Ratcliffe and David John Young – are salvaged from the water and buried in the Algemene Begraafplaats at the Keern in Hoorn.

The other three crew members – James William Ralph, Bernard Spencer John Akehurst and John David Dill-Russell – are still missing. They have probably found a seaman’s grave at the bottom of the IJsselmeer. Their names have been added to the Runnymede Memorial Panels in Englefield Green, England, which commemorate the names of all missing English airmen of World War II.

The danger of this German anti-aircraft defense system (Himmelbett-Verfahren) is so great that the Allies try to undermine it by attacking, among other things, Leeuwarden Air Base. That is also the mission of the small English fighter-bomber, type Mosquito MK VI, which takes off from the base station Manston from Monday to Tuesday night of 5 to 6 June 1944. At around 02:00 am the Mosquito flies over the IJsselmeer, east of Scharwoude near Hoorn. Pilot Arthur Whitten-Brown and navigator Victor George Brewis are both Lieutenants of 605 Squadron Fighter Command RAF.

De Havilland Mosquito gets its name from its size and weight. Since the fighter plane is almost entirely made of wood, it is lightweight and can hold a lot of fuel. This typical English aircraft contains Rolls-Royce engines and is therefore fast and manoeuvrable. It is also called the Wooden Wonder or Mossie by the English. The aircraft has four 20mm on-board guns in the nose as standard. In addition, the aircraft can be equipped with 1,800 kilograms of bombs or eight missiles under the wings. It is not known which bombs Whitten-Brown’s aircraft had with it, but it is known that it had a so-called Intruder Mission at Leeuwarden Air Base that night and therefore had bombs or rockets or a combination of these with it.

The English airmen are also armed themselves, but the British planes do not have a Ball turret from which they can fire like the American bombers and are therefore more vulnerable to enemy night fighters. The Germans adjust their tactics accordingly by attacking the bombers from behind and below. German night fighters have a slanting visor pointing upwards and on-board guns. They can almost always fire effectively from close range, which, in combination with the German radar system, is sometimes completely unexpected for the English crew members.

Arthur Whitten-Brown Senior and Victor Brewis

It is not known whether this also happened with the Mosquito of Arthur Whitten-Brown and Victor Brewis. But the plane crashed into the IJsselmeer on June 6 around 2 a.m. Arthur’s body was not found until June 22 in the IJsselmeer. A week before, on June 15, Victor’s body washes ashore near Hoorn. Both crew members are also buried in the general cemetery at the Keern in Hoorn. The news of Arthur’s death hits his father – also called Arthur – so much that the already fragile health of this aviation pioneer is no longer okay. Arthur Witten-Brown senior was the first to fly across the ocean in 1919 – as navigator on the first non-stop transatlantic flight. Read more about it here.

But what about that green sign at the entrance gate of the cemetery on the Keern? If a cemetery has one or more Allied war graves, then there is such a sign with the inscription ‘Oorlogsgraven van het Gemenebest – Commonwealth War Graves’ at the entrance. War graves do not always look like in the movies: in long rows with the same stones or crosses as on the large war graves. Often the family of the Dutch war victims has placed a grave monument themselves and the graves are therefore not easy to discover (look at the site of the War Graves Foundation: there the indication of the berth is indicated, usually with a photo of the grave monument). Foreign military graves, however, are often easily recognizable, such as the four on the Keern. The graves of four English airmen on the Keern received an official gravestone from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. These are next to each other and are identical.

To commemorate the war victims, the board of ‘Comité 40-45 Hoorn’ lays flowers on the war graves on the 4th of May every year. The English pilots are commemorated with a flower arrangement, but flowers are also laid on the Dutch war graves. These are the eight graves listed at the Dutch War Graves Foundation. The grave of Hendrik Danner, who died in 1944 near Muiden as a result of war, is also included in this tribute. Because the Dutch war graves were not easy to find, red geraniums were planted on them, just like on the four English graves. (Additionally, there are also Dutch war graves in Hoorn at the Roman Catholic Cemetery on Drieboomlaan.)